Debussy’s Gamelan – The 1889 Exposition and the Birth of Impressionism

Claude Debussy was an influential French composer, and one of the most significant figures in Western classical music. He is known for his innovative use of tonality and harmony, which paved the way for a wide range of musical styles in the early 20th century. In this article, we will explore how Debussy’s composition ‘Gamelan’ reflects the cultural influences he encountered during his visit to Indonesia in 1889, which played an important role in shaping the birth of Impressionism.

Early Years and Influence

Debussy was born on August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. He began his musical education at a young age and studied piano and composition at the Paris Conservatory. In 1880, he traveled to Italy and later spent two years studying in Italy and Austria. During this time, he became fascinated with non-Western music and instruments, which would later influence his compositional style.

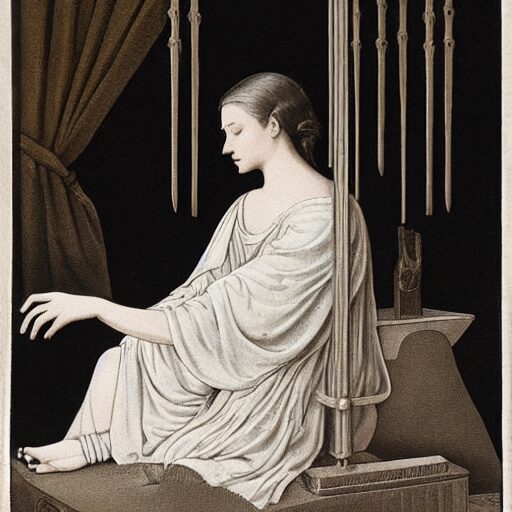

In 1889, Debussy visited Indonesia, where he was exposed to the Gamelan, a type of orchestra originating from Java. The Gamelan is characterized by its use of percussion instruments, particularly gongs, drums, and xylophones. During his stay in Indonesia, Debussy transcribed several Gamelan pieces, which would later become part of his composition ‘Gamelan’.

The 1889 Exposition and the Birth of Impressionism

The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris was a significant event that brought together artists and musicians from around the world. Debussy saw this as an opportunity to showcase French music on the international stage. He submitted his composition ‘Gamelan’ for the fair, which was meant to be part of the “musique de salon” section.

Although ‘Gamelan’ did not win any prizes, it caught the attention of several critics and composers. One such critic was Vincent d’Indy, who wrote a review praising Debussy’s composition. D’Indy saw ‘Gamelan’ as a departure from traditional tonal music, which was a characteristic of French musical style at that time.

Gamelan: A Composition Ahead of its Time

The title ‘Gamelan’ refers to the Indonesian orchestra Debussy encountered during his visit. The composition is characterized by its use of unconventional scales and tonality. Debussy used this new style to create a sense of tension and release, which was a departure from traditional French music.

In an interview, Debussy described his compositional approach: “I do not write music for the ear, but for the eye.” This statement reflects his innovative approach to composition, which paved the way for Impressionism.

Conclusion

Debussy’s ‘Gamelan’ is a testament to the composer’s innovative and adventurous spirit. During his visit to Indonesia in 1889, Debussy was exposed to new musical styles and instruments that influenced his compositional style. The composition of ‘Gamelan’ marked an important turning point in French music history, paving the way for the birth of Impressionism.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was a renowned French composer and pianist. His compositions include ‘Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun’, ‘La Mer’, and ‘ Pelléas et Mélisande’.

Gamelan is an Indonesian orchestra originating from Java, characterized by its use of percussion instruments.