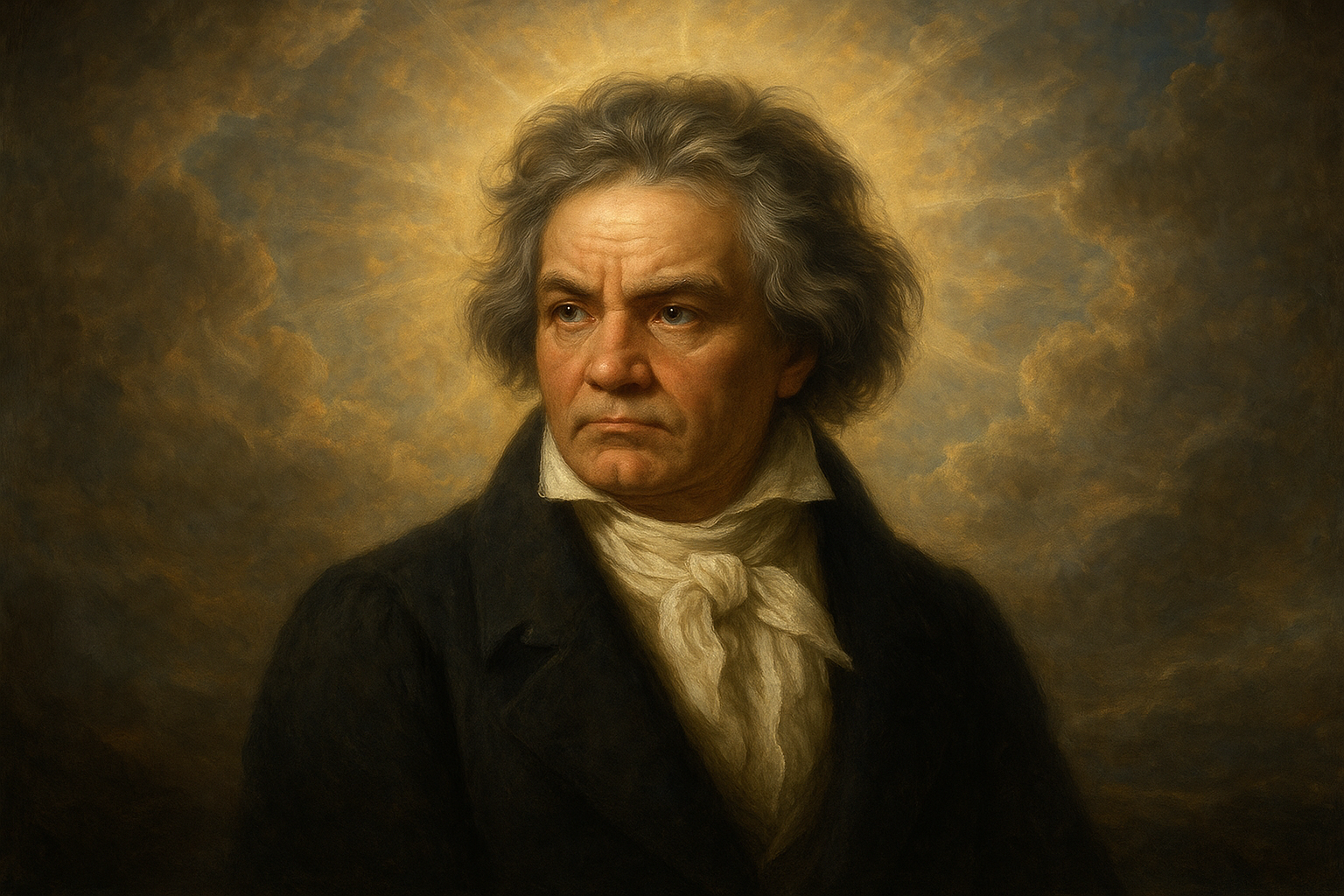

A Transcendental Sound: Beethoven’s Late Quartets and the Divine

Few works in the classical music repertoire evoke the sense of the divine as powerfully as Ludwig van Beethoven’s late string quartets. Written during the final years of Beethoven’s life, these compositions are not only a testament to his genius but also an exploration of profound spiritual themes. The late quartets offer listeners an experience that borders on the transcendental.

The Quintessence of the Late Period

Beethoven’s late quartets, composed between 1825 and 1826, include the Opus 127, 130, 131, 132, 133, and 135. These works mark a period when the composer, almost entirely deaf and in poor health, was at the height of his creative powers. As musicologist Joseph Kerman notes, “The late quartets are not so much music as they are a spiritual quest, Beethoven facing eternity.”1

Consciousness and the Sublime

Beethoven’s immersion in deep contemplation is evident in the profound emotional range of these works. The String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131, for instance, is a testament to Beethoven’s ingenuity, featuring seven interconnected movements played without pause. As Paul Nettl observes, “This quartet seems to breathe a spirituality and an understanding of the infinite.”2

“This is music that disturbs and moves like no other.”

– Arnold Schoenberg

Theological Undertones

Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 is particularly noteworthy for its slow third movement, “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart” (“Holy Song of Thanksgiving of a Convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian Mode”). Its solemnity and spiritual depth have led many to see it as a prayer or meditation. According to musicologist Michael Steinberg, this movement is “not merely programmatic but a radiant vision of the divine.”3

A Bridge to the Heavenly

The quality of the late quartets to bridge towards the transcendent can be partly attributed to Beethoven’s own struggles and search for meaning. In the complexity and daring nature of the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133, Beethoven challenges the audience to transcend its temporal existence. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno once remarked that “Beethoven’s late quartets sound like they come from another world, communicating the unspeakable.”4

Elements of the Divine in Music

- Introspection: The movements often reflect Beethoven’s philosophical musings, infusing music with an aspect of contemplation.

- Novel Structure: Free from conventional form, the quartets explore new territories, providing a metaphor for spiritual journey.

- Symbolism: The use of harmonic language, like the Lydian mode, evokes ancient religious traditions.

The Universal Language of Music

Many scholars argue that Beethoven’s late quartets communicate a universal spiritual message, transcending cultural and temporal boundaries. In one of his letters, Beethoven himself articulated this transcendence: “Music is indeed the mediator between the spiritual and sensual life.”5

In reopening our ears and hearts to Beethoven’s late quartets, we not only appreciate their complexity and beauty but also their ability to communicate the ineffable. In the words of Leonard Bernstein: “Beethoven’s music is truly the sound of the universe speaking through us all.”6

Conclusion

Beethoven’s late quartets remain an enduring testament to the composer’s visionary legacy. They challenge and inspire, compelling us to consider the deeper resonances between art and spirituality. Through them, listeners continue to find not just a reflection of their own souls, but glimpses of the divine. As we listen, we are reminded of the power of music to transcend human suffering, uniting the earthly with the ethereal.

- Kerman, Joseph. “Beethoven’s Late Style.” The New York Review of Books, 2001.

- Nettl, Paul. “Beethoven’s Late Quartets: A Study in the Progress of Time.” The Schiller Institute, 1999.

- Steinberg, Michael. “The Beethoven Quartets and the Language of Spirituality.” Classical Music Quarterly, 2003.

- Adorno, Theodor W. “Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music.” Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998.

- Beethoven, Ludwig van. Selected Letters, ed. and trans. by Emily Anderson, 1961.

- Bernstein, Leonard. “The Joy of Music.” Amadeus Press, 1959.