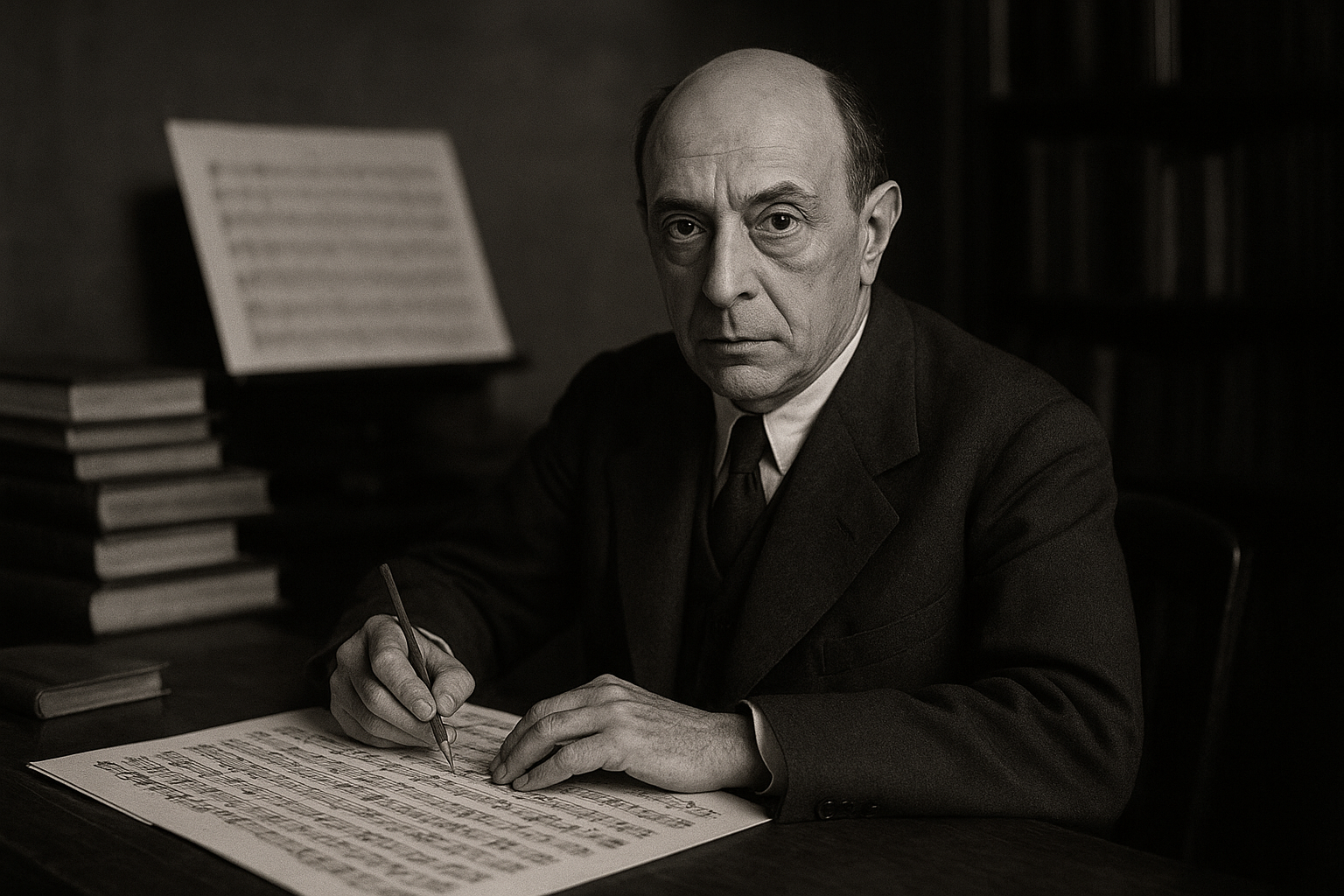

The early 20th century saw a groundbreaking shift in the landscape of Western classical music, largely heralded by the innovative works of Arnold Schoenberg. As the father of atonal music, Schoenberg revolutionized how we conceive musical harmony and composition, forging a path that would influence generations of composers.

The Historical Context

In the late romantic era, composers like Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss pushed the boundaries of tonal music to their limits. The increasing use of chromaticism and complex harmonic structures hinted at a looming change. It was within this fertile ground that Schoenberg began his pivotal exploration of dissonance and tonality.

- Chromaticism: The use of notes outside the traditional key, creating tension and color.

- Extended Tonality: Expanding traditional key structures to include more notes and harmonies.

The Break from Tradition

In 1908, Schoenberg composed his landmark String Quartet No. 2, which boldly abandoned traditional tonal centers. This work paved the way for his subsequent development of the twelve-tone technique, a method that treats all twelve notes of the chromatic scale as equal, thereby eliminating the hierarchy of tones that define traditional tonality. In his Second String Quartet, Schoenberg himself declared, “I have stretched the rules to breaking point.”

“Schoenberg’s invention of atonal music moved the aesthetic boundaries substantially.” — The Guardian

In 1921, Schoenberg formalized this method, leading to works such as his Pierrot Lunaire. This cycle of 21 melodramatic pieces foreshadowed later developments in expressionism, aligning music with movements in visual arts and literature. It marked the shift towards a more abstract, emotive form of expression.

The Impact on Modern Music

Schoenberg’s atonal music was initially met with controversy and resistance. Yet, his dogged pursuit of abstraction and expressionism found adherents among his pupils, including Alban Berg and Anton Webern, who furthered the serialism movement. Schoenberg’s influence extended beyond classical music, affecting jazz, film scores, and popular music production.

While Schoenberg himself remarked, “There is still much to explore in this new world of sounds,” his contributions are indelibly woven into the fabric of modern music. His atonal explorations marked not just a new method of composition but heralded a new way of hearing music, challenging audiences and composers alike to consider the very nature of harmony and melody.

In conclusion, Schoenberg was not merely a composer; he was a visionary who disrupted musical tradition, ushering in an era of new possibilities and defining what we now understand as modern music.